Empowered Aid

“I want to talk about food. At times, you find that we girls or women we find difficulties with the distributors. These distributors who are distributing. They come and tell that, ‘if you fall in love with me, I will add you more food, or for the cooking oil you will get a big share.’ So you end up… after they have realized the food is about to come, they move around corning girls or women, that, ‘if you really fall in love with me, I will add you food.’ So those are big challenges.”

-Uganda, Participatory group discussion with South Sudanese adolescent girls living in Uganda as refugees

Purpose

At the Participatory Action Research Workshops, women or girls from the refugee community selected which types of aid to study. All tools & manuals developed are available under the “Manuals & Toolkits” tab.

Empowered Aid is a multi-year, multi-country participatory action research project led by the Global Women’s Institute with operational partners CARE and URDA in Lebanon, and International Rescue Committee and World Vision in Uganda. Working alongside women and girls—as those most affected by SEA and other forms of gender-based violence—the study examines the mechanisms through which humanitarian aid is delivered, and how these processes might inadvertently increase the risks of SEA, in order to better address these risks. Its goal is to support the creation or adaptation of aid delivery models that actively work to reduce power disparities and give women and girls a sustained voice in how aid is delivered.

Empowered Aid is funded by the U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (BPRM).

Methods

Empowered Aid is feminist, participatory action research (PAR) that recognizes women and girls as contextual safeguarding experts and engages them as co-producers of knowledge, supported to safely take an active role in asking and answering questions about their own lives. PAR proactively acknowledges and addresses power imbalances— in this case, between men and women; aid workers and those receiving aid; and researchers and those being researched. Just as participation lies at the center of accountable humanitarian response, it is a critical element for research that seeks to shift power imbalances.

The first phase is grounded in ethnographic work in which women and girls document their observations of SEA risks in relation to accessing four different types of aid, which they selected: food, shelter, WASH, cash (in Lebanon), and fuel & firewood (in Uganda). In the second phase, their observations guide the identification and prioritization of ways to improve aid distributions, which are then pilot with NGO operational partners (implementation science). The third phase, slated to begin in late 2020, will focus on research uptake and peer-to-peer capacity building in a third country, tentatively Bangladesh. In this phase, women and girls and other research team members in Uganda and Lebanon will share what they've learned and build networks around women and girl-led, participatory action research in refugee settings.

The first phase of participatory action research was conducted over three months in partnership with the International Rescue Committee in Uganda and CARE International in Lebanon. In both Lebanon and Uganda, SEA was reported as occurring across all types of aid explored, in all stages of the distribution cycle—from communicating and receiving information; to registering or being verified for aid; at the distribution site; traveling to and transporting aid from these sites; and safely storing aid. In addition, women and girls reported multiple barriers to reporting cases of SEA, including lack of knowledge or faith in reporting mechanisms, stigma and other negative repercussions from community and family members, and the normalization of SEA meaning that for many, they and their families and communities see it as the cost of receiving life-saving assistance.

- To better understand how aid distributions may create or reinforce opportunities for sexual exploitation and abuse of women and girls.

- Ethnographic fieldwork with refugee women and girls

- To identify, prioritize, and test options for improving current distribution models & post-distribution monitoring tools.

- Implementation science, pilot tests

- To disseminate, validate and replicate findings in a third country, including peer-led networking & training among women & girl researchers.

- Research uptake, dissemination, network-building

Findings

Reports, manuals, toolkits and other study materials can be found on the "Empowered Aid Resources" page, available through the menu above or by clicking here.

Sexual exploitation & abuse associated with types of aid:

Food

“Like the boda boda guys. You agree with him to bring your food home. Yet he has intentions of corning you. Now he will carry for you the food and of course the distance is long and after carrying the food he will end up telling you, ‘I have helped you, I want you.’"

– Uganda, Participatory group discussion with with South Sudanese adolescent girls living in Uganda as refugees

WASH

“As the boreholes are made, they are just far, they are far from the settlement you will follow. If there is no water here, we go and fetch from those boreholes, if you go alone you can be able to be raped. Secondly these latrines they do not have lights in it, and they are made just one, you may be four to five, they may be five to four families all using this same latrine and someone coming somewhere can also come and enter. You may not know. You enter minus light, you will go and get someone there, you can be raped. And also, these latrines if I have no power, I may request for some to come and dig for me, and this person if he digs will demand sex from me. These are some of the violence that we normally face within the water and sanitation that we are having around.”

– Uganda, Qualitative interview with South Sudanese adolescent girl living in Uganda as a refugee

Shelter

"These humanitarian workers also having been constructing houses. So, they called some girls, to come and helping them in cooking…So they tell them that they will pay after finishing the work. So, these girls agreed and started working after finishing the work, the girls asked their money and these guys changed that… They started these relationships with these girls. They are forcing these girls to fall in love with them and since these girls are in the camp, they need their money. So, they fall in love with these boys. They end up impregnating the girls, and now they disappeared from the settlement…So girls suffer most.”

– Uganda, Participatory group discussion with South Sudanese adolescent girls living in Uganda as refugees

Cash

“Employees who work in the United Nations or another organization, ask women for something in return for aid, like an amount of 100 000 LBP or 100 dollars, in return for going out together. A lot of things like that happened. A lot of women were deprived of aid. I know a girl who was deprived of aid. She used to receive 100 dollars a month, and the person who was giving her the money, asked for her hand in marriage, but she refused, because he has a family, and she didn’t want to ruin his family, so he stopped giving her the 100 dollars.”

– Lebanon, Qualitative interview with Syrian woman living in Lebanon as a refugee

Fuel and Fire

"To me firewood again is the most common, with many things happening. Like last year when we went, we found a man in the bush saying that, ‘if you want firewood, start to move with condoms, next time if you come without them, I will kill you.”

–Uganda, Participatory group discussion with South Sudanese adolescent girls living in Uganda as refugees

South Sudanese women living in Uganda as refugees, and members of the Empowered Aid team, take part in data analysis through the Action Analysis Workshop. Here, they are voting to prioritize recommendations arising from phase one findings on how to improve safety and risk in aid distribution. For more, see the workshop facilitation guide under the “Manuals & Toolkits” tab.

Sexual exploitation and abuse at different stages of the distribution process:

When communicating or giving information about distributions

“...so later on when you realize that you are a PSN that you were like raising a concern so that they will maybe construct for you a house the other people who are working maybe with some organization, they may tend to say since when you wanted me to build for you a house or maybe you wanted me to raise your information your issue up so that they will build you a house you have to accept me, it had happened that I have seen there was a woman who had that case so she was like she wanted a house so that man tend say since when you want a house for me to forward your challenge ahead you have to accept me first before I forward your case not until the man slept with woman and the woman was given house.”

–Uganda, Qualitative interview with South Sudanese woman living in Uganda as a refugee

During registration exercises

“Like mainly about sometimes when they don’t understand why they’re not getting aid; this is the main problem. Like why are we excluded and why others are include[d], you know this criteria. And other problems on the site are being able to actually come alone or being used to, like by her brother, they could use the element that she’s the woman, and she’s weak, it’s just like an abusive power.”

–Lebanon, Key informant interview with humanitarian personnel

At the point of distributions

"Of course, there are a lot of people take advantage of the crisis. They might not let an older woman in but will let the younger woman in and ask her for perform certain acts in exchange of the services. They ask girls for certain things to give them services. If the girls refuse, they will withhold the service, but the service is not that great in the first place. They take advantage of little girls the most because 1. They are still young and don’t know how to handle such situations and 2. They need the service that is being offered at their home and 3. They think about their family before themselves and might be pressured into agreeing. I heard about a center that offered such services and only let in young girls (not women or men). You would hear girls crying and running quickly out because they were being harassed inside the center.”

-Lebanon, Qualitative interview with Syrian adolescent girl living in Lebanon as a refugee

Storing or maintaining aid

“Like they are some houses which had been build [sic] like if the windows are not properly made others will come that let me help you repairing it immediately after repairing it he demand for sex may be will love you that is the thing.”

–Uganda, Qualitative interview with South Sudanese woman living in Uganda as a refugee

Transporting items home

“Yes, I was in a taxi once and a girl got into it too. There’s a man who winked at her and suggested that he pay for her fare. This is financial exploitation. He wants sexual favors in return.”

–Lebanon, Community participatory group discussion with Syrian refugee men living in Lebanon as refugees

Empowered Aid's findings demonstrate how a distribution system that does not meet women and girls’ needs for food, WASH, fuel/firewood, cash, and shelter materials in safer ways inadvertently opens up space for exploitation and abuse by aid as well as non-aid actors. The reports and briefs on this page detail these findings further and contain targeted recommendations for humanitarian actors—including government and donors—to take forward.

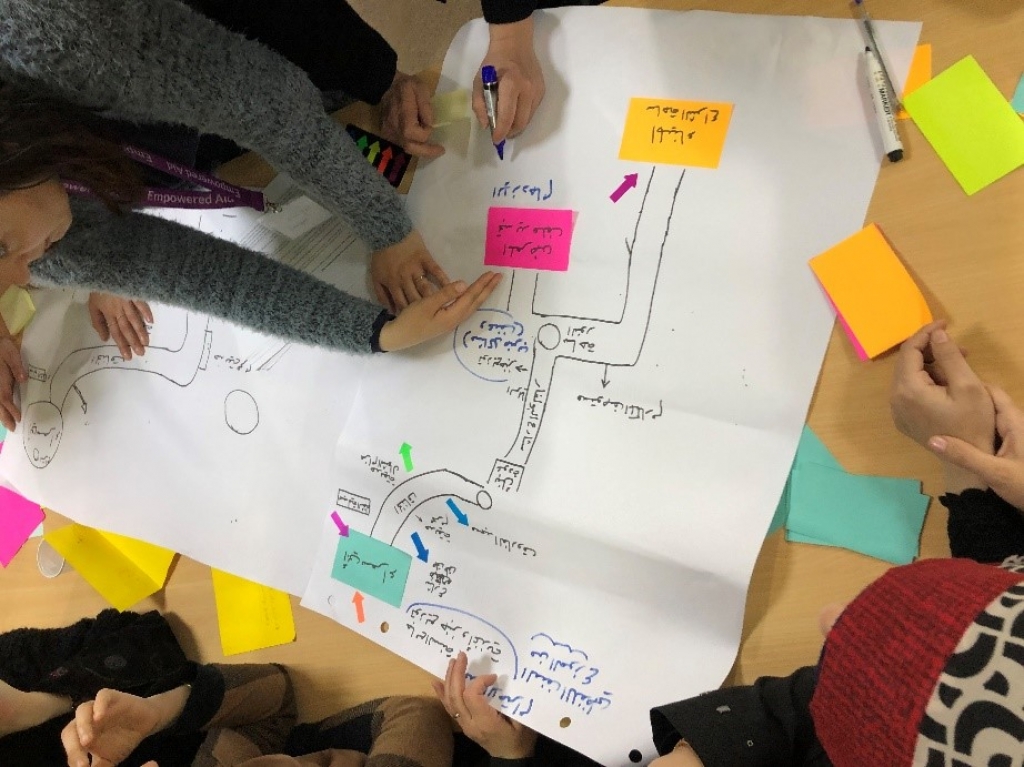

CARE Lebanon staff lead Syrian refugee women researchers through a community mapping exercise during the Participatory Action Research Workshops in Tripoli. Within Empowered Aid, community mapping was used to support collaborative identification of safe or unsafe places and time in women and girls’ communities. For a facilitation guide, see the PAR Workshop guide or Phase 1 Toolkit under the “Manuals & Toolkits” tab.

Recommendations for Humanitarian Aid Stakeholders

“He might protect himself with the organization’s name, so no one is going to believe her…being in need exposes her to such exploitation.”

Participatory group discussion with Lebanese host community girls

1. INCLUDE WOMEN & GIRLS IN PROGRAM DESIGN

Aid distribution systems must be adapted to more fully meet women and girls’ needs for shelter materials, cash assistance, fuel & firewood, WASH, and food items in ways that minimize opportunities for SEA by aid as well as non-aid actors. The most important way to do that is to ensure women & girls are part of program design.

2. INCREASE ACCESS TO GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE SERVICES

Increase survivors’ access to gender-based violence services—such as healthcare, psychosocial support, and case management—while ensuring access to such services is not contingent on reporting specific instances of abuse, in recognition of the powerful deterrent this can be.

“Like the boda boda guys. You agree with him to bring your food home. Yet he has intentions of corning you. Now he will carry for you the food and of course the distance is long and after carrying the food he will end up telling you, ‘I have helped you, I want you.’"

Participatory group discussion with South Sudanese adolescent girls living in Uganda as refugees

3. RECOGNIZE WOMEN & GIRLS AS CONTEXTUAL SAFEGUARDING EXPERTS

Recognize women and girls as experts in contextual safeguarding and actively engage them in mechanisms designed to improve aid processes and protect against SEA.

4. INCREASED ACCOUNTABILITY AMONG SENIOR MANAGEMENT

Specifically, senior management and safeguarding leads must take responsibility to reflect on their organization’s role in creating a ‘conducive context’ for abuse. Attend to the settings and people who represent ‘causes for concern’, dig deeper into these concerns, and act on them. Ensure perpetrators are held to account.

“She cannot tell anyone because she is using that as an opportunity for adding her food ration, so she will not tell anyone about her situation. Because if she tells anyone about her situation, this person will follow the person who is doing that to her, and the person may lose job which will make her also lose her addition of food ration.”

Participatory group discussion with Ugandan host community boys

5. PROMOTE TRANSPARENT AND PARTICIPATORY M&E PROCESSES

M&E staff also have a key role to play. Transparently monitor safety and risk at all points in the distribution process. Share this information with aid actors and community structures. This allows for collective, proactive responses to dangerous situations, and contributes to greater accountability in mitigating SEA (and other forms of GBV).

6. IMPLEMENT EXISTING IASC PSEA & GBV GUIDELINES

Use Empowered Aid’s findings and tools to support training—particularly with frontline staff and SEA focal points. Further implement existing IASC PSEA & GBV Guidelines.

Programmatic Recommendations to Make Aid Distributions Safer: Common Findings Across Lebanon (urban) & Uganda (rural) Sites

Refugee women & girls generated and prioritized these recommendations to make aid distribution safer (for more on this process, see the “Action Analysis Workshop Facilitation Guide” under the Manuals & Toolkits tab on our Resources page).

Implement sex-segregated lines at distribution points to avoid women and girls being pushed out of line and/or harassed, which can put them at risk of SEA when they are exploited by those who offer to take them to the front of the line or otherwise expedite the process.

Provide transportation support for those traveling long distances to collect food, WASH, and other items. Plan distributions in collaboration with women’s committees/leaders, and discuss transport support options (including in-kind or cash/vouchers) for groups identified as particularly vulnerable.

Ensure more women aid workers, volunteers, and leadership structures are involved in aid distribution processes. Involving women in aid deliver increases accountability; and helps women and girls feel safer when aid workers visit their homes.

More security at distribution points (particularly noted for WASH and fuel/firewood aid in Uganda and cash assistance/ATMs in Lebanon) by mixed-sex teams who are well-supervised and trained to proactively mitigate SEA and other forms of violence.

Create accompaniment systems and improve information sharing among women. Women and girls who move in groups, or are together when aid workers or contractors come to their homes, report feeling less vulnerable to SEA and other risks.

Increased community sensitization on what constitutes GBV / SEA and how to make a complaint, to increase the number of people in a community who hold this information. Delivered in diverse ways to reach different groups, including those with low literacy, speak minority languages, and/or adolescents.

Visual representation of Syrian refugee women and girls’ recommendation of ensuring more women aid workers, volunteers, and leadership structures are involved in aid distribution processes.

Visual representation of South Sudanese refugee women and girls’ recommendation of encouraging and supporting formal and informal accompaniment systems for women and girls when collecting and transporting aid.

Context-Specific Recommendations from Syrian Refugee Women & Girls Living in Lebanon

Financial aid through cash assistance to reduce SEA-related vulnerabilities. Women and girls noted particular risks for widows and female-/child-headed households

Pre-determined, assigned times for households to go, in groups, to collect aid from distribution points. This was suggested in order to avoid overcrowding and disorganization that women and girls identified as risk factors for SEA. Reducing the number of people at distribution points is also safer in light of COVID-19 public health regulations.

Household-level delivery and/or repairs can help mitigate risks women and girls face when leaving their homes, if conducted in gender-sensitive ways—for example, by teams of sex-matched aid workers (e.g., women workers visiting women’s homes) or mixed-sex teams (e.g., at least two aid workers with at least one being a woman).

Information sessions on safely and securing withdrawing money from ATMs, targeted to women and girls and delivered in diverse formats.

Closer supervision of aid staff/contractors/volunteers involved in distributions, including filing and following up on complaints. Women & girls calls for increased accountability of aid workers through more oversight by NGO/UN staff who understand the risks that could lead to SEA, and the importance of creating a safe environment in which women and girls can access aid.

Context-Specific Recommendations from South Sudanese Refugee Women & Girls Living in Uganda

Information, communication, and dispute resolution sessions with host community members to manage tensions proactively. Access to fuel, firewood, grasses for shelter, and water points, can require negotiation with host community members which may put women and girls at risk of SEA and other forms of violence.

Support women and girls to organize response mechanisms to assist each other when they feel unsafe or at risk (sounding an “alarm”). Traveling isolated distances or having to negotiate with host communities for access to key resources may leave women and girls vulnerable to SEA. Supporting them to create systems that allow for sounding alarms and getting help can be lifesaving.

More community and direct support to safely construct houses; particularly targeting vulnerable groups of women and girls, such as female-headed households, widows, or unaccompanied adolescent girls, to reduce their risk of SEA.

Better lighting and closer WASH distribution and collection points. Women and girls highlighted distance to WASH distribution points or facilities (i.e. water taps, latrines) as something that puts them at risk, as well as lack of lighting at these sites.